The Trump administration is less than a month away from releasing its latest annual budget request, but so far no one is saying officially whether it will feature another attempt to revive the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository.

The White House’s fiscal 2021 spending proposal is due on Feb. 10, a senior administration official confirmed this week following reports by Politico and other news outlets.

In each of its last three budget plans, the administration sought money for licensing the geologic repository in Nevada at the Department of Energy and Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Congress has rebuffed the request every time.

The Energy Department and White House Office of Management and Budget this week did not say whether Yucca Mountain will make an appearance in the budget plan for the fiscal year beginning Oct. 1. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission does not expect to comment on its funding proposal prior to the release date, a spokesman said Tuesday.

Robert Halstead, executive director of the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects, said he expects Trump to take a fourth swing at funding. “In fact, I would be quite surprised if there is no request for new Yucca Mountain funding,” he told RadWaste Monitor by email in December.

“I have no inside information, but I would hope the Administration would continue to request money for Yucca Mountain licensing in fiscal year 2021,” Steve Nesbit, a former Duke Energy executive and chair of the American Nuclear Society’s Nuclear Waste Policy Task Force, also said by email last month. “Completing the licensing process is consistent with enacted law and it is also in the best interests of the United States.”

The Nuclear Energy Institute, the Washington, D.C.-based trade group for the nuclear industry, concurred. But a senior representative played down the likelihood of congressional appropriations for Yucca Mountain in an election year that also features the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump now underway in the Senate.

“it is an election year, so who knows,” said Rod McCullum, NEI senior director for fuel and decommissioning, said in a Wednesday telephone interview. “We’re hopeful that they will do something similar to what they did in past year. But we have no ability to handicap that, I have no prediction on what they will do.”

New Secretary Dan Brouillette and other leaders at the Energy Department, though, have suggested they will make another attempt to restart Yucca licensing — noting in various appearances on Capitol Hill that it is the law.

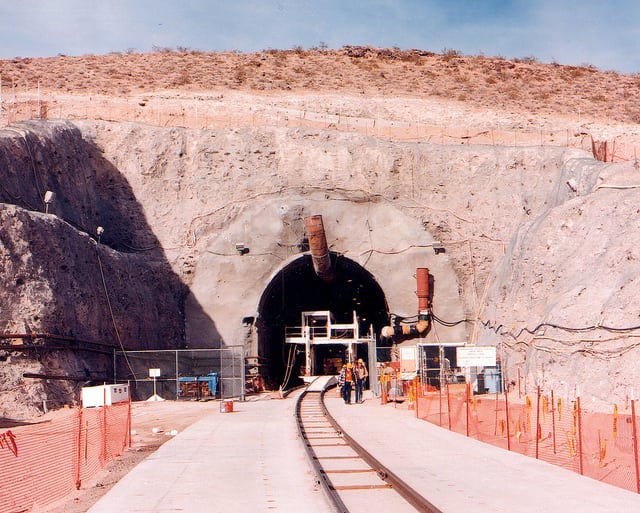

Congress in 1982 assigned the Energy Department to build a permanent disposal site for the nation’s stockpile of spent fuel from commercial nuclear power plants and high-level radioactive waste from defense nuclear operations. It then amended the Nuclear Waste Policy Act in 1987 to direct that the repository be built under Yucca Mountain, roughly 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

Today, more than 70 active and retired nuclear sites around the nation store roughly 82,000 metric tons of used fuel. That amount grows by 2,000 to 2,500 metric tons annually, according to DOE.

The Energy Department is nearly 22 years past the Jan. 31, 1998, deadline to begin accepting waste for disposal, without little to show for its efforts. The agency filed its Yucca Mountain license application with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 2008, during the George W. Bush administration, only to have the Obama administration defund the proceeding two years later.

That stasis is largely where things stand today. The Obama administration never got far in its “consent-based” approach for siting separate repositories for civilian and defense waste, but returning to Yucca Mountain has not worked so far for its successor.

Should a Democrat be elected in November, it seems probable the White House would stop asking for money to license Yucca Mountain. In campaign stops in Nevada, candidates have made a point of opposing forcing the state to accept the repository.

“So the problem with the Yucca Mountain is it’s not got the consent of those who would be impacted, and I don’t think it’s an acceptable solution as long as there is not that kind of consent,” candidate Pete Buttigieg, former mayor of South Bend, Ind., told The New York Times.

For the current fiscal 2020, the White House wanted roughly $150 million for licensing operations at the NRC and DOE. House and Senate Appropriations committees zeroed out that request in favor of separate spending packages focused on promoting interim, centralized storage of spent fuel rather than final disposal. But there was no money for either approach in the final full-year budget signed into law in December – for reasons that remain a bit hazy.

The initial Senate 2020 appropriations package covering DOE and the NRC was heavy on language authorizing standup of an interim storage program, McCullum noted. That apparently ran afoul of concerns in the upper chamber about authorizing programs in appropriations measures, he said.

The corresponding House energy and water appropriations bill had focused on funding – $47.5 million for integrated waste management, with $25 million of that intended specifically to advance consolidated interim storage.

“So why couldn’t they have conferenced on the House bill, I have no idea,” McCullum said. However, another concern might have been spending money on temporary storage in the absence of a repository.

Two separate corporate teams are seeking NRC licenses to build consolidated interim storage facilities for used nuclear fuel in Texas and New Mexico. Elected officials in New Mexico have been particularly vocal in their worry that interim storage could become permanent if the United States remains unable to build its final disposal facility.

Even with steady funding, licensing the repository would take years to complete, and there is no assurance the NRC would approve the application. The Yucca Mountain repository program itself was estimated as of 2008 to cost $96.2 billion from inception in 1983 to site closure in 2133, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Nevada’s state leaders and congressional delegation show no sign of retreating from their long-held opposition to accepting other states’ radioactive waste – their concerns ranging from the potential for water infiltration or earthquakes to release radiation into the environment, to damage to the state’s crucial tourism business. Led by Halstead, the state filed more than 200 contentions against the Energy Department license application and has promised more if the proceeding resumes.

The American Nuclear Society’s Nesbit, though, said the federal government has spent more than $10 billion to demonstrate the viability of the Yucca Mountain site. Staff at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has determined the federal property is capable of taking and storing the waste in a safe manner, he said.

Nesibit added there is benefit to resuming licensing even if it ultimately does not lead to approval of the Nevada repository.

Even a negative result on Yucca Mountain would offer insight into the viability of applicable NRC regulations and the federal government’s approach for demonstrating that a repository location is safe, he said. Those lessons could be applied to a potential search and license application for a separate site.

“We think that, ultimately whether it’s at Yucca Mountain or somewhere else, the country’s going to need a repository. If you can show that you can successfully navigate the licensing process with the repository at Yucca Mountain, then I think that’s going to give added assurance to the public,” Nesbit said during a November interview. “And it’s also going to demonstrate for other potential repository sites that there’s a path forward to make it through our regulatory system.”