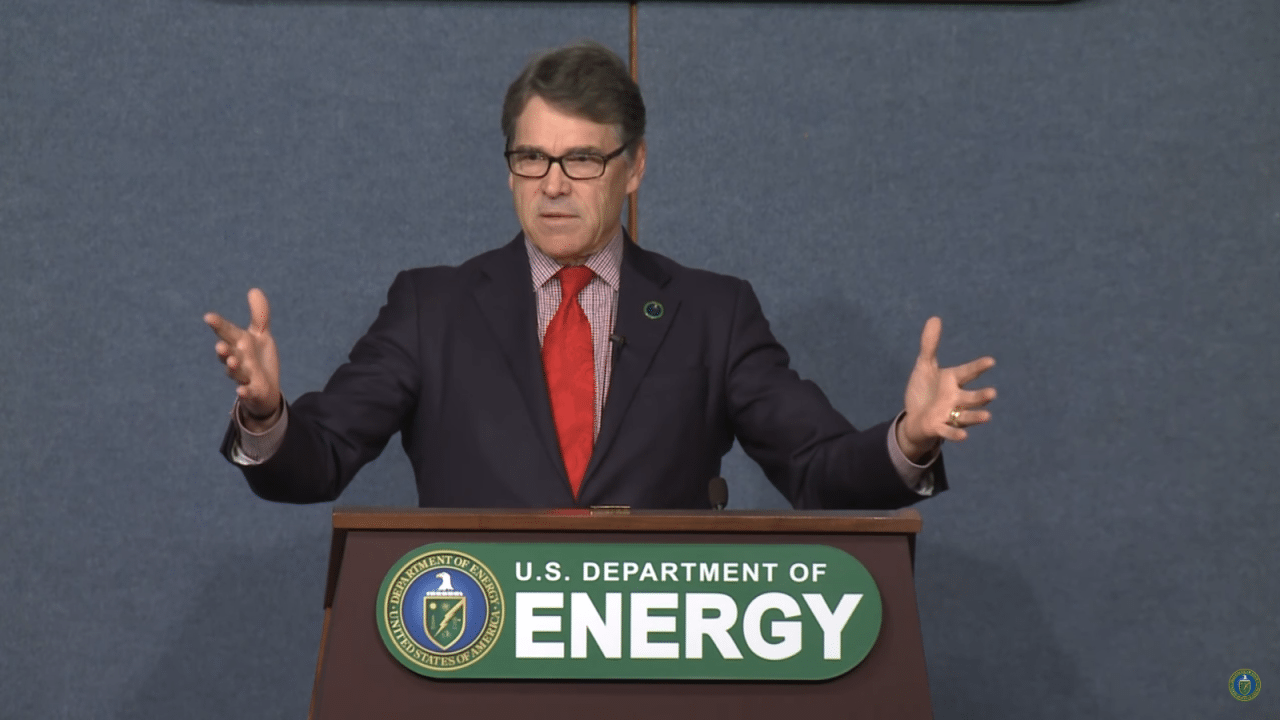

In congressional testimony Thursday, Energy Secretary Rick Perry stressed the importance of getting spent nuclear fuel away from the power plants that generated it, even if that means finding “alternatives” to a planned permanent repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada.

“I don’t want to get stuck that Yucca’s the only place that you can go,” Perry told members of the House Energy and Commerce energy subcommittee.

Perry said he wanted to avoid a scenario in which “if Yucca doesn’t happen, then we’re gonna set here with 38 states having high-level nuclear waste in various places around in their states that are not secure [and] that have potential for a disaster to occur, whether it’s man-man or a natural disaster.”

The Energy boss said it would be “wise” to consider “alternatives” to Yucca. As he has in prior appearances on Capitol Hill, Perry suggested the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Waste Isolation Pilot Plant near Carlsbad, N.M., a facility in Texas owned by the financially troubled Waste Control Specialists, or maybe “some sites that we haven’t even talked about or we hadn’t thought about yet,” might be suitable interim storage sites for the tens of thousands of tons of spent nuclear fuel generated by U.S. power plants.

The last time Perry suggested these sites might be suitable for interim nuclear-waste storage, he drew swift blowback from Nevada’s congressional delegation and governor. After the dust settled, Perry quickly walked back the remarks, saying DOE had made no final decision on interim waste sites.

However, Perry was unwavering on one point: He wants Congress to appropriate the $120 million the Donald Trump administration requested in May for DOE to resume its Yucca Mountain license application with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). In 2010, the Barack Obama administration effectively canceled that application.

“The most important priority now is for Congress to appropriate the funding so that we can reopen the nuclear waste program and finish the Yucca Mountain licensing,” Perry said.

The Trump administration’s plan to resume DOE’s Yucca license application sparked a buzz in the nuclear-waste-management community in the spring, but the hype has cooled considerably after a summer of political headbutting in Congress.

In the House, appropriators supported the administration’s plan. In the Senate, where the staunchly anti-Yucca Sen. Dean Heller (R-Nev.) wields enough political power to hold votes on Trump-supported legislation and nominees hostage, appropriators provided not a cent for the repository.

The standoff dragged on all summer and now might not be resolved until early December. Last month, having failed to pass any 2018 spending bills, Congress approved a short-term stopgap budget that froze federal spending at fiscal 2017 levels. There was no money in DOE’s budget for Yucca Mountain in the budget year that ended Sept. 30.

Stuck in this holding pattern, Perry began Thursday trying to manage expectations by telling lawmakers that licensing Yucca is fundamentally different from actually building it.

Substantially all of Perry’s testimony on Yucca came in response to questions from Rep. John Shimkus (R-Ill.): the spearhead of the congressional effort to open the facility.

Earlier this year, Shimkus introduced the 45-page page Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 2017: a bill that, in Shimkus’ words Thursday, “provides the department (DOE) the tools to successfully complete the adjudication of the pending license for [the] Yucca Mountain repository; authorizes DOE to pursue a temporary storage program while the disposal facility is completed; [and] allows the repository of the host state to constructively partner with DOE to mitigate potential impact.”

Shimkus’ bill has since accrued more than 100 co-sponsors in the House, a quarter or so of them Democrats, and awaits a floor vote after breezing through the Energy and Commerce Committee in late June.

Over the summer, sources familiar with behind-the-scenes negotiations in the House thought Shimkus’ bipartisan bill might get a floor vote earlier this month. That never happened, and Shimkus himself has since said he is not rushing to put the measure before the whole House. A House aide has said the bill would likely be voted on pursuant to a rule yet to be written by the House Rules Committee, and that the timing of a floor vote was up to GOP leadership in the lower chamber.

Shimkus’ bill would result in some $1.8 billion in new government costs for the 10 years ending in 2027, according to a recent report from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. That includes a little less than $300 million in payments to states and local governments affected by Yucca, and a little more than $1.5 billion in lost government revenue, since the bill would bar fees on nuclear power until NRC authorizes DOE to build Yucca.

Under House rules, any bill that would result in new spending must be bundled with an offset. The Rules Committee can waive that rule.

Shimkus’ bill would eventually allow DOE to tap into the Nuclear Waste Fund to pay for Yucca. This pot of money was created more than three decades ago — by the Nuclear Waste Policy Act Shimkus’ proposal would amend — to pay for a permanent waste repository. The government collected more than $30 billion for the fund from fees on nuclear power before suspending the fee in 2014. DOE needs Congress to appropriate money from the fund each year, however.

In a larger sense, the Congressional Budget Office acknowledged Shimkus’ bill “would not significantly change the overall magnitude of the long-term costs the government will incur under the [Nuclear Waste Policy Act].” In all, the office said, Yucca will still cost “tens of billions of dollars over multiple decades.”

Meanwhile, Perry allowed Thursday that Yucca’s opponents — substantially all of Nevada’s congressional delegation, plus the state’s governor and attorney general — might yet find vindication of their claims that Yucca is an unsafe place to store nuclear waste for thousands of years.

“Those that are against this [Yucca], they may find out, you know, through this [licensing] process, that they were right. Or that they’re not,” he said. “But until we get to the end of that process, we’re not going to know.”