The Trump administration this week again proposed to fund resumption of licensing for the long-planned, long-delayed Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository in Nevada.

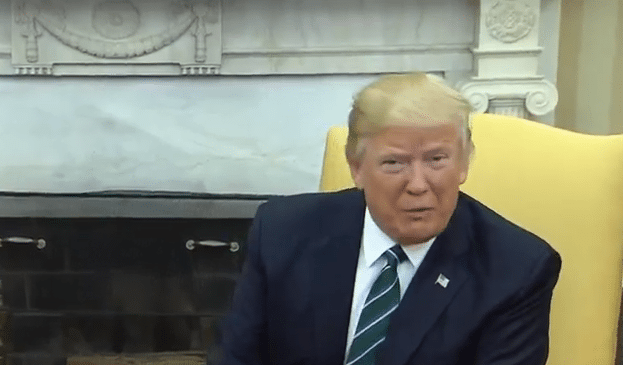

The state’s congressional delegation immediately pushed back against the latest White House budget plan, reminding President Donald Trump that he suggested last fall he would oppose the disposal facility.

The Department of Energy and Nuclear Regulatory Commission, respectively the applicant and adjudicator for the license, together requested just over $154 million for the federal 2020 fiscal year. That is down by more than $10 million from their last proposals for interim storage and permanent disposal of radioactive waste – nearly all of which would have gone for Yucca Mountain licensing.

In rolling out the broad overview of its spending plan Monday, the White House said “The Budget … demonstrates the Administration’s commitment to nuclear waste management by supporting the implementation of a robust interim storage program and restarting the Nuclear Regulatory Commission licensing proceeding for the Yucca Mountain geologic repository.”

In its new budget request, the Department of Energy said it wants $116 million for its Yucca Mountain and Interim Storage Program. That would be a $4 million reduction from the fiscal 2019 proposal for resuming repository licensing and developing a temporary storage capacity to expedite removal of spent fuel from utilities.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission this week asked for $38.5 million for Yucca Mountain operations. That is down from $47.7 million sought for the current budget through Sept. 30.

Congress zeroed out the agencies’ requests to fund this work in both fiscal 2018 and 2019.

Speaking to reporters Monday morning, senior DOE officials said the request for Yucca Mountain funding is in line with federal law. In the 1982 Nuclear Waste Policy Act, Congress ordered the department to build a permanent repository for the nation’s spent nuclear power reactor fuel and high-level radioactive waste from defense operations – a stockpile now sized at about 100,000 metric tons and stored at dozens of locations. In its 1987 amendment to the legislation, Congress directed that the federal property about 100 miles from Las Vegas be the only site considered for the disposal facility.

The Energy Department submitted its license application to the NRC in 2008, but the Obama administration halted the proceeding two years later. Licensing has remained frozen for the better part of a decade, despite the Trump administration efforts to revive Yucca Mountain.

More details about the DOE and NRC budget requests could be included in their full budget justifications, due Monday.

The money would be drawn from the federal Nuclear Waste Fund, established under the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to finance development, licensing, and construction of the repository.

At the NRC, the $38.5 million would cover 77 full-time equivalent employees for adjudication of the DOE license application. The NRC arrived at that number “in order to move smartly toward being able to execute the program in three years. We have to hire a lot of lawyers, given that that’s where it is in the process,” according to Maureen Wylie, NRC chief financial officer.

As an intervenor to the license review, the state of Nevada successfully filed 218 technical contentions against the application before the process was suspended, on issues including waste transport and storage and the potential impact on Las Vegas. State officials have said they anticipate filing another 30 to 50 contentions if the proceeding is revived.

The regulator’s prior budget request for fiscal 2019 would have covered 124 full-time equivalent personnel.

“We’ve been working really hard to extend efficiency and effectiveness to all parts of our program,” Wylie said. “And so we made a concerted effort to review the requests in the past and we determined that we could achieve roughly the same objective for less resources.”

Other work that could be funded in fiscal 2020 would be re-establishing the database of documents related to the adjudication and potentially establishing a new location for the proceeding. The over 3 million existing documents from the Licensing Support Network have been shifted to the NRC’s public online document library.The site previously used in the adjudication, near McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas, was dismantled; the NRC in October formally suspended its search for a new site in the absence of a congressional appropriation.

Leaders in Nevada this week made it clear they intend for none of this to happen, reaffirming their long-held opposition to importing other states’ nuclear waste.

“This is dead on arrival. The president is ignoring the voices of Nevadans by trying to restart Yucca Mountain – a project that wasted $19B already,” Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nev.) tweeted just hours after the White House budget went out.

Similarly, Rep. Dina Titus (D-Nev.) said Trump’s proposal breaches his “promise” to Nevadans during an October trip to the state. While campaigning for then-Sen. Dean Heller (R-Nev.), Trump acknowledged widespread opposition to the project. “I think you should do things where people want them to happen, so I would be very inclined to be against it. We will be looking at it very seriously over the next few weeks,” he told a local television station.

The White House and federal agencies afterward never commented on any potential reconsideration of the nuclear waste disposal approach.

During a House budget hearing Tuesday, acting White House Office of Management and Budget Director Russ Vought told Rep. Steven Horsford (D-Nev.) that Trump is “not breaking his promise and he is very open to the conversation,” the Nevada Current reported.

Cortez Masto, Titus, and their Nevada colleagues last week introduced two bills that would put the foot on development of Yucca Mountain as a radioactive waste repository: one would require DOE to obtain written consent from impacted state, local, and tribal jurisdictions before moving ahead with any disposal site; the other would prohibit licensing, preparation, or construction of the repository until Congress receives a report from the White House Office of Management and Budget on potential job-creating alternative uses for the federal property.

As lawmakers on both sides of the political divide noted this week, Congress ultimately sets appropriations levels for federal agencies. The House in recent years supported the White House requests for Yucca funding, even adding $100 million to the DOE proposal last year. The Senate has focused on interim storage and zeroed out Yucca. The end result has been no money for either approach.

Democrats retook control of the House in January following the November midterm elections. Reports from Capitol Hill indicate Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) pledged to oppose any funding for Yucca Mountain in order to garner support from Nevada lawmakers for becoming House majority leader again.

Meanwhile, influential Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) has said he supports advancing both Yucca Mountain and interim storage in the upcoming budget. Alexander chairs the Senate Appropriations energy and water development subcommittee, which writes the first draft of the budget bill for DOE and the NRC. In recent years, the panel has focused on funding interim storage at the expense of the repository program.

At deadline Friday for RadWaste Monitor, neither congressional Appropriations Committee had scheduled hearings on the Energy Department or Nuclear Regulatory Commission budget requests. Alexander, though, said his subcommittee would meet shortly after next week’s recess, Politico reported.

NRC Budget

In total, the NRC is requesting $921.1 million for the budget year beginning Oct. 1, up by $10.1 million from the enacted budget but down from $970.7 million from its fiscal 2019 request.

Of that total, $759.6 million would be derived from NRC licensee fees and the remaining $161.5 million from congressional appropriations – including the $38.5 million for Yucca Mountain.

The budget plan would cover 3,062 full-time equivalent employees, a reduction of 44 from the current level. These personnel support a long list of functions, including facility licensing and inspections, developing new regulations, enforcement, research, and emergency response.

From the fiscal 2014 budget to the proposal for fiscal 2020, the NRC has cut its budget by 15 percent and full-time equivalent staffing by 21 percent. The reductions have been driven by Project Aim and other rightsizing efforts, after the agency in prior years grew in anticipation of increased regulatory work for a nuclear power renaissance that never materialized.

“We’ve been working hard to enhance our culture of innovation and transformation so that we’re ready to remain effective across a range of future scenarios,” Wylie said. “We’ve had some ups and downs over the course of the last 20 years and we believe that we need to be more cognizant of the variety so that we can respond more quickly as the world evolves.”

Fiscal 2019 funding for nuclear reactor safety would be reduced by $9.9 million, from the enacted level of $459.4 million to the requested $449.5 million. The count of full-time equivalent personnel in this budget areas would drop from 1,919 to 1,824.

The reductions are largely due to a decreased workload following the October closure of the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station in New Jersey and the anticipated retirements this year of the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station in Massachusetts and reactor Unit 1 at the Three Mile Island plant in Pennsylvania, Wylie said.

On the nuclear materials and waste safety line item, the NRC would increase from $134 million and 515 FTEs to $165.7 million and 564 FTEs. That spike would be driven by funding and personnel for Yucca Mountain, with reductions in decommissioning and low-level waste and other line items based on decreased workload.