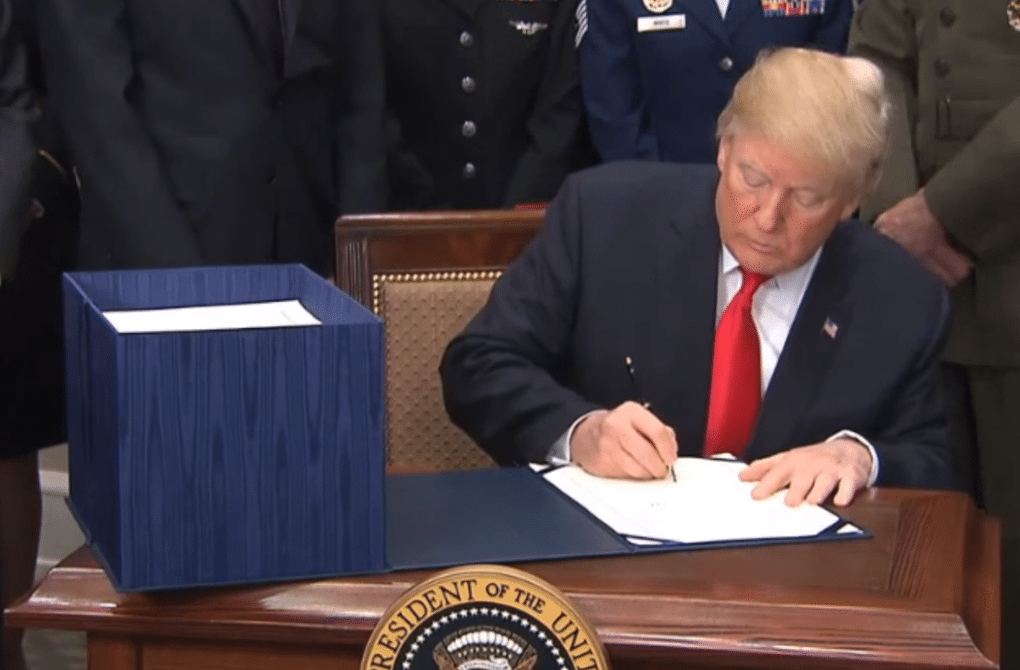

President Donald Trump this week signed the fiscal 2018 National Defense Authorization Act, which makes it harder to move plutonium pit production out of New Mexico, calls for a competition to design a new nuclear warhead for ballistic missiles, and authorizes…