A senior U.S. arms control negotiator on Thursday would not endorse limiting the U.S. nuclear arsenal to the 1,550 strategic warheads prescribed by the New START treaty with Russia if the treaty expires in 2026 without a new accord in place.

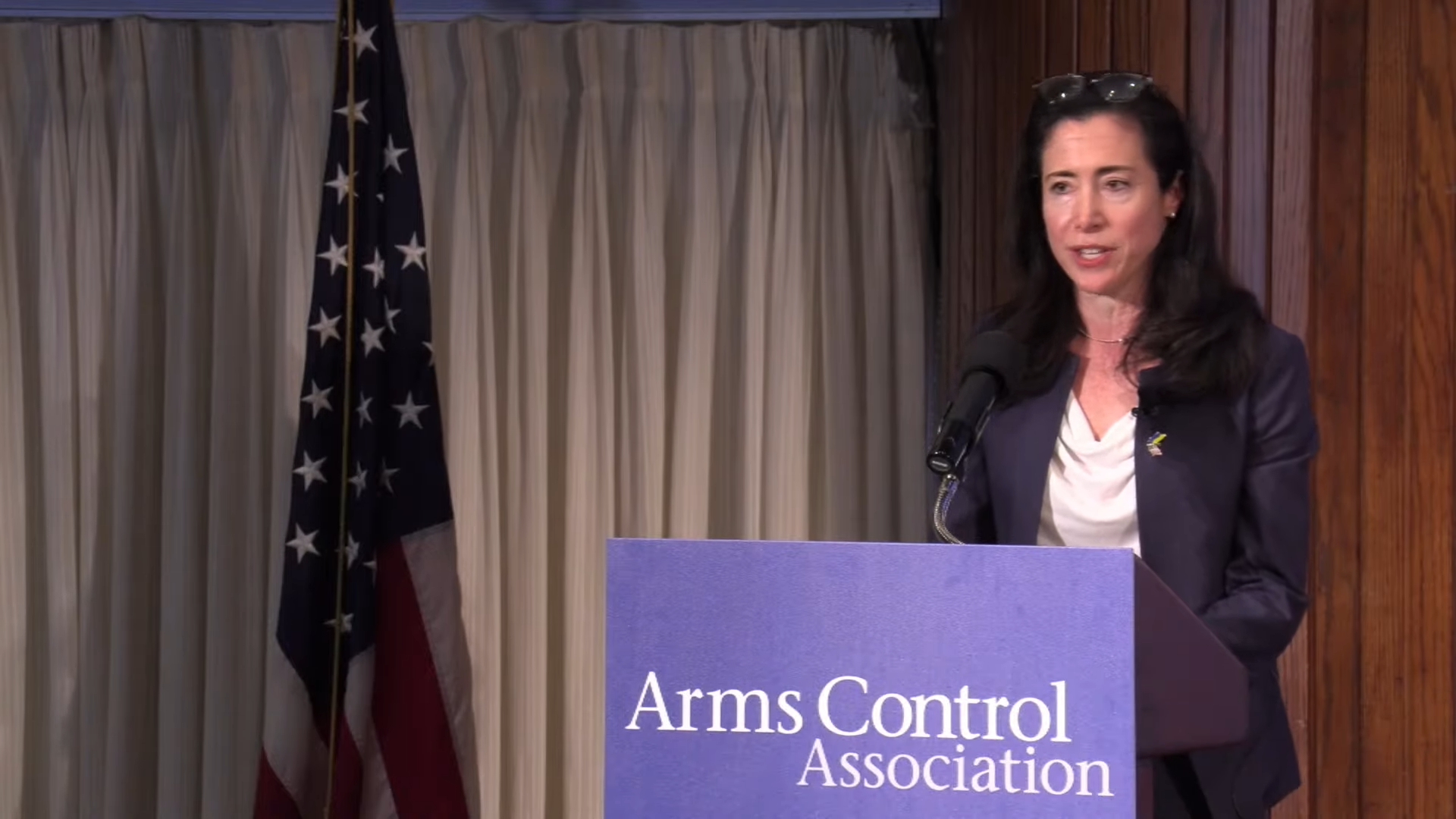

“I don’t think we should sort of right now figure out what is the right path because I think there could be other venues or opportunities,” Mallory Stewart, assistant secretary of state for arms control, verification, and compliance, said during the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting in Washington. “My bureau is actively working to sort of figure out what we could put forward should the opportunity arise, but we should keep all options open for what we can do moving forward.”

Stewart, speaking in public only for the second time since her confirmation in late March, was responding to a question from Carol Giacomo — chief editor of Arms Control Today, the official publication of the disarmament advocating group — who asked whether the Biden administration might consider, if the last existing nuclear-arms-control treaty between Washington and Moscow lapses without a successor, “a unilateral U.S. declaration that you would continue to adhere to the NEW START limits as long as Russia did?”

New START, which entered force in 2011 during the Barack Obama administration, lets the U.S. and Russia deploy no more than 1,550 warheads across 700 intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and heavy bombers, while possessing no more than 800 deployed and non-deployed bombers, ICBM, and SLBM launchers. Bombers count as a single warhead, under the treaty.

Extended for five years in January 2021 by Biden and Vladimir Putin, the Russian president and de facto dictator, New START runs through Feb. 4, 2026.

Russia in February invaded its neighbor, Ukraine, for the second time in less than a decade, freezing bilateral talks about a New START follow-up treaty.

“When we engaged the final time with Russia in January of this year, we demonstrated our good faith in talking about each and every one of the articles in their proposed [follow-up] treaty,” Stewart said. “[W]ithin a month [Russia] had invaded Ukraine. And so it’s very hard right now to understand how we can sort of acknowledge and accept that they would be willing to engage with us in good faith.”

Ahead of the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting, the New York Times published similar comments, which it attributed to a senior official in the Biden administration.

Also at the annual gathering of arms control professionals and proponents, Stewart sought to frame the Biden administration’s decision to cancel the nuclear sea launched cruise missile, or SLCM-N, as an internal Department of Defense recommendation that percolated up to a President who willing to accept it.

“It was a whole of government decision,” Stewart said. “There was a very extensive Department of Defense-led Nuclear Posture Review working group that considered across the board all of the existing systems or those in train and collectively made the recommendation to the President that this particular system didn’t make sense to continue going forward. We’ve just recently heard from the Department of Defense again that it was a large amount of money, that it was blocking out other capacities, it was not seen as useful in several contexts.”

In congressional hearings this spring, top uniformed officers, including the commander of U.S. Strategic Command have gone on record opposing cancellation of SLCM-N.

Republican lawmakers have vowed to oppose the Biden administration’s recommendation to cancel the weapon and the sea-launched variant of the W80-4 warhead that the National Nuclear Security Administration was supposed to start work on this year. The warhead is the intended tip for the Air Force’s Long Range Standoff weapon cruise missile.