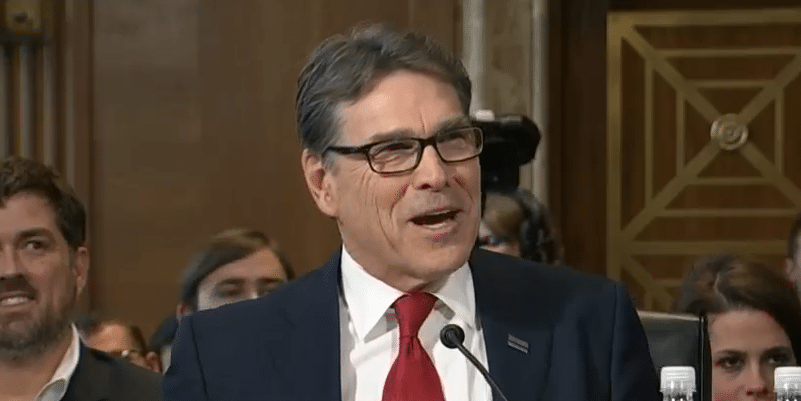

Rick Perry on Thursday announced his resignation as the Donald Trump administration’s first secretary of energy after more than two-and-a-half years on the job.

In a published letter to President Donald Trump, Perry said he would resign “later this year” from the Cabinet. Dan Brouillette, the deputy secretary of energy, will then take over as acting secretary.

Perry’s nuclear legacy is tough to clearly identify. The former Texas governor — whose passion since being sworn into federal service in March 2017 has been promoting American sources of energy for electrical utilities and transportation — seldom spoke publicly about the nuclear weapon- and weapon-cleanup missions that account for roughly 60% of DOE’s annual budget. He also was unable to persuade Congress to fund licensing for the planned nuclear waste repository under Yucca Mountain, Nev.

In his resignation messages, Perry did not say why he was leaving the administration, or exactly when. He did say that he would return to Texas. Many Cabinet secretaries, in Republican and Democratic administrations, stick around only for one term or half a term.

Perry’s departure was telegraphed well in advance. Earlier this month, media reported that sources said the DOE boss would resign this autumn to seek work in the private sector. On Thursday, the Wall Street Journal published an exclusive and candid interview with Perry. Later that day, DOE dropped the neatly edited video announcing Perry’s departure.

Reports earlier this month indicated Brouillette could be nominated to replace Perry. Trump, on his way Thursday to a campaign rally in Texas, told reporters “We already have his replacement.” He did not identify that person.

On Friday, Perry told CNBC that, post-DOE, he might consider charitable work, such as a prison ministry, or perhaps “an opportunity to work with people, to bring power to the billion plus people in the world that don’t have electricity.”

Perry did not say how long he would stick around, though he implied, in his video farewell, that it would not be much longer. In the roughly four-minute piece, interspersed with video clips and stills of his visits around the DOE complex and abroad, the outgoing Energy boss said there would be much work to do “in these upcoming weeks.”

Right up until October, Perry mostly skirted the controversies of policy and conduct that have ensnared, and sometimes forced from office, other members of Trump’s Cabinet.

On Oct. 10, the House Intelligence Committee subpoenaed Perry’s records of talks with Ukrainian officials. The subpoena is part of an impeachment inquiry led by the House’s Democratic majority, and is based on allegations that Trump used the powers of his office to block congressionally appropriated defense aid to Ukraine, unless the newly elected president of that country, Volodymyr Zelensky, agreed to investigate the son of Joe Biden: the former vice president and current contender for the Democratic Party’s 2020 presidential nomination.

No Progress on Yucca Mountain

In three budget proposals during Perry’s tenure, the Energy Department annually sought funding to resume the long-stalled licensing of the Yucca Mountain geologic repository for high-level radioactive waste and spent fuel from U.S. nuclear power plants. It struck out twice and appears headed to rejection again for the current fiscal 2020.

“Perry worked the issue hard. He was unable to secure a commitment from Sen. [Lamar] Alexander for funding,” one informed source said by email Thursday.

Alexander (R-Tenn.) is chairman of the Senate Appropriations energy and water subcommittee, which writes the first draft of annual Energy Department-funding bills. He has been a strong proponent of building centralized, temporary storage sites in order for DOE to more quickly meet its legal directive to remove spent fuel from nuclear facilities.

The source said Perry personally met with nearly two-dozen senators last fall to press for funding for Yucca Mountain in both fiscal years 2019 and 2020. All the meetings were productive, except for the talks with Alexander, the source said.

In appearances over the years before congressional committees, Perry has said he supported restarting licensing of the Yucca Mountain disposal site as required by law. He has suggested, though, that he believes there are other options for disposing of the waste, assuming approval from Congress.

Perry reaffirmed that position Wednesday during a press briefing on small modular reactors, POWER magazine reported.

“The administration is still working toward finding the solutions,” according to Perry. “We’ve got waste, I think, in 38 different states that we’ve got to deal with. And the idea that we’re just going to leave this waste in these temporary sites that weren’t built for any long-term storage at all, it’s not appropriate. Frankly, it’s immoral.”

The 1982 Nuclear Waste Policy Act directed the Energy Department to by Jan. 31, 1998, begin disposal of radioactive waste. The legislation was amended in 1987 to direct that the waste be buried in a repository under federal land about 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

The agency filed its construction and operations license application with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 2008 during the George W. Bush administration, but the Obama administration defunded the proceeding two years later. The Obama DOE tried to start a new “consent-based” approach to selecting waste storage and disposal locations, but the Trump administration went back to Yucca Mountain after taking office in January 2017.

The Republican-led House supported the Trump Energy Department’s licensing funding requests for fiscal 2018 and 2019. However, the Senate approved appropriations legislation prepared by Alexander’s panel that zeroed out funding for Yucca in favor of money for interim storage. In the end, negotiators blanked both approaches in the final spending bills.

The Energy Department asked for about $110 million for licensing for fiscal 2020, which began Oct. 1. The House, now with a Democrat majority following the November 2018 midterms, in June instead passed legislation that would provide nearly $50 million for “integrated management” of nuclear waste, including $25 million for interim storage. The Senate Appropriations Committee also gave nothing for Yucca Mountain, instead committing to fund a pilot program for interim storage. That bill is awaiting a vote by the full Senate as early as next week. In the meantime, the federal government is operating on a short-term budget that keeps funding a fiscal 2019 levels through Nov. 21.

The state of Nevada has long opposed being forced to become home to other states’ radioactive waste at federal directive. The mistrust was exacerbated when state leaders learned DOE’s semiautonomous National Nuclear Security Administration had last year quietly shipped a half-metric ton of plutonium for storage at a facility in Nevada.

“I wish I could say I was going to miss Secretary Perry, but that is not the case,” Robert Halstead, who leads the state’s battle against Yucca Mountain as executive director of the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects, said by email Friday. “Secretary Perry did nothing to fix the broken nuclear waste program. Three times he asked Congress for more than a hundred million dollars to restart the Yucca Mountain repository project. He is responsible for the secret plutonium shipments to Nevada. He didn’t just fail to make the relationship between the Department of Energy and Nevada better. Secretary Perry made the relationship worse.”