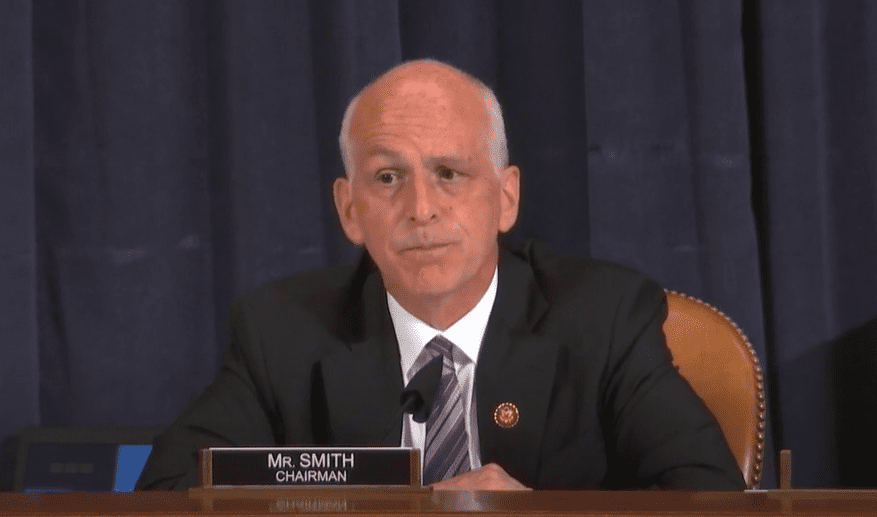

After failing to build a plutonium recycling plant at the Savannah River Site after 20 years of planning and billions spent, the chair of the House Armed Services Committee said this week he doubts the National Nuclear Security Administration can turn the failed project into a plutonium pit factory.

“I do not trust Savannah River,” said Smith, referring to the DOE site in Aiken, S.C., where the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has proposed turning the moribund MOX facility into the Savannah River Plutonium Processing Facility. “I’ve been down to see the building down there and I don’t know if you can just convert a MOX facility into a pit production facility.”

Smith made the remarks Tuesday at a virtual press roundtable hosted by the Washington-based Defense Writers Group. He spoke to reporters a day after the NNSA approved the Savannah River pit plant’s critical decision one review, which formalized the agency’s plan to build the factory from partially completed MOX facility — even though this first detailed review of the project revealed it would cost $6.9 billion to $11.1 billion to finish by 2032 or 2035.

The high end of that estimate is two-and-a-half times more expensive and five years later an estimate NNSA floated publicly in 2018.

Yet for all Smith’s bite at Tuesday’s press event, he also appeared to endorse more or less that same pit production strategy the NNSA has proposed for the next decade or so, which involves beginning production of new pits at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in 2024 and ramping up to 30 pits annually by 2026.

“I’ve also heard that it’s possible that we could get more than 30 a year out of Los Alamos,” Smith said Tuesday. “So I’m not going to exaggerate that, but you could get potentially 40 or 50. I think that is where we should focus our efforts in the near term, and the near term is like a decade.”

The NNSA by law has to have its pit-production complex ready to produce 80 pits annually by 2030. In June, the agency’s acting administrator, Charles Verdon, said the NNSA could not meet that goal because of the projected delay at the Savannah River pit plant, but that the two-pronged pit complex was still the fastest way of hitting the target throughput.

NNSA formalized its plan to build a pair of pit plants in 2018.

‘I Don’t Think Life Extension of Minuteman III is Going to Get Us There’

The planned Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) intercontinental ballistic missile would be the first beneficiary of any new pits cast at Los Alamos and Savannah River, and Smith said this week that the program is a better idea than once again extending the service life of the Minuteman III missile GBSD is supposed to replace.

GBSD will eventually get W87-1 warheads, which will be fresh copies of the existing W78 warhead, except with new plutonium pits. The first GBSD missiles are scheduled to deploy with W87-0 warheads: weapons from the current Minuteman III fleet that will be adapted for the successor rocket in flight tests lifting off no sooner than December 2023.

“[W]e’re not going to kill the GBSD program,” Smith said Tuesday. “Minuteman III will be fine for a little while [but] that does not mean that we need to have as many [intercontinental ballistic missiles] as the previous posture review suggested, or even that we need that leg of the triad.”

As a rule of thumb, Smith said, nuclear weapons spending should be kept at a minimum until the White House finishes its nuclear posture review. An administration official testified in June that the review should be published in January.

“I would support spending the least amount of money possible to keep our options open, depending on what the president decides in the nuclear posture review, and also depending on what he could begin to negotiate with Russia or China on arms control agreements,” Smith said Tuesday.

The Biden administration’s 2022 budget request, released May 28, does not really reflect Smith’s preferences for near-term nuclear weapons spending. Neither does a 2022 appropriations bill released Tuesday by the House Appropriations Committee. Each would essentially continue the spending trends the Trump administration forecast for the fiscal year that starts Oct. 1.

Under the bill, GBSD would get some $2.5 billion, around $100 million less than requested but nearly $1 billion more than the 2021 budget. The Long Range Standoff weapon air-launched cruise missile would get about $580 million, which is $25 million less than requested but more than $100 million above the 2021 appropriation.

However, the House-authored bill would axe the proposed low-yield, nuclear-tipped Sea Launched Cruise Missile, according to a summary of the legislation. The missile could carry a variant of the W80-4 warhead the NNSA is preparing for the air-launched missile.

The full House Appropriations Committee was scheduled to mark up the subcommittee’s bill on July 13. The full committee then plans to mark up an energy and water development spending bill, which includes the DOE budget, on July 16.

At deadline, the House Armed Services Committee that Smith chairs was not scheduled to mark up its annual National Defense Authorization Act, the policy bill that accompanies the Pentagon’s annual appropriation, until September.

Editor’s note, 07/08/2021, 2:13 p.m. Eastern time: the story was corrected to show that a House Appropriations panel’s bill proposed no funding for a sea-launched nuclear cruise missile.