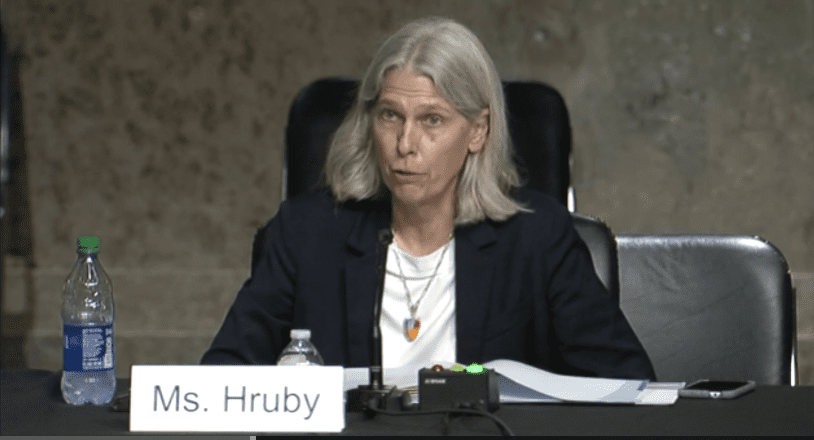

Though the National Nuclear Security Administration plans to dramatically ramp up plutonium pit production around the time a key arms control treaty expires in 2026, there are no plans to test fire any weapons, agency Administrator Jill Hruby said Monday in New…