Vienna – The United States and Russia have not held any discussions about resuming full implementation of the bilateral plutonium elimination agreement that Russian President Vladimir Putin suspended in early October, a senior U.S. State Department official said here Wednesday.

Thomas Countryman, acting undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, said in an interview with NS&D Monitor that while the two countries have maintained contact on issues related to nuclear security, nonproliferation, and arms control, “we haven’t talked about them changing their decision on the [Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement].”

The 2000 deal requires each country to dispose of 34 metric tons of nuclear weapon-usable plutonium. Moscow suspended its participation, asserting that the Obama administration, among other actions, failed to uphold its end of the agreement by trying to cancel the Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility project at the Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site in South Carolina – the agreed-upon U.S. disposal method under the PMDA – in favor of an alternative plutonium dilution and disposal method.

The National Nuclear Security Administration said this week the administration “remains firmly committed to disposing of surplus weapon-grade plutonium” through the dilute and dispose approach, which it called “a known and proven process that will be less than half the cost of the MOX option, have far lower risks, and can be implemented decades sooner.”

Russian withdrawal from the agreement, Countryman said, “is a fit of diplomatic pique that has little practical consequence. The Russians have said that they will dispose of those 34 tons as they had planned, that it will not be moved into any kind of weapons-usable stockpile.”

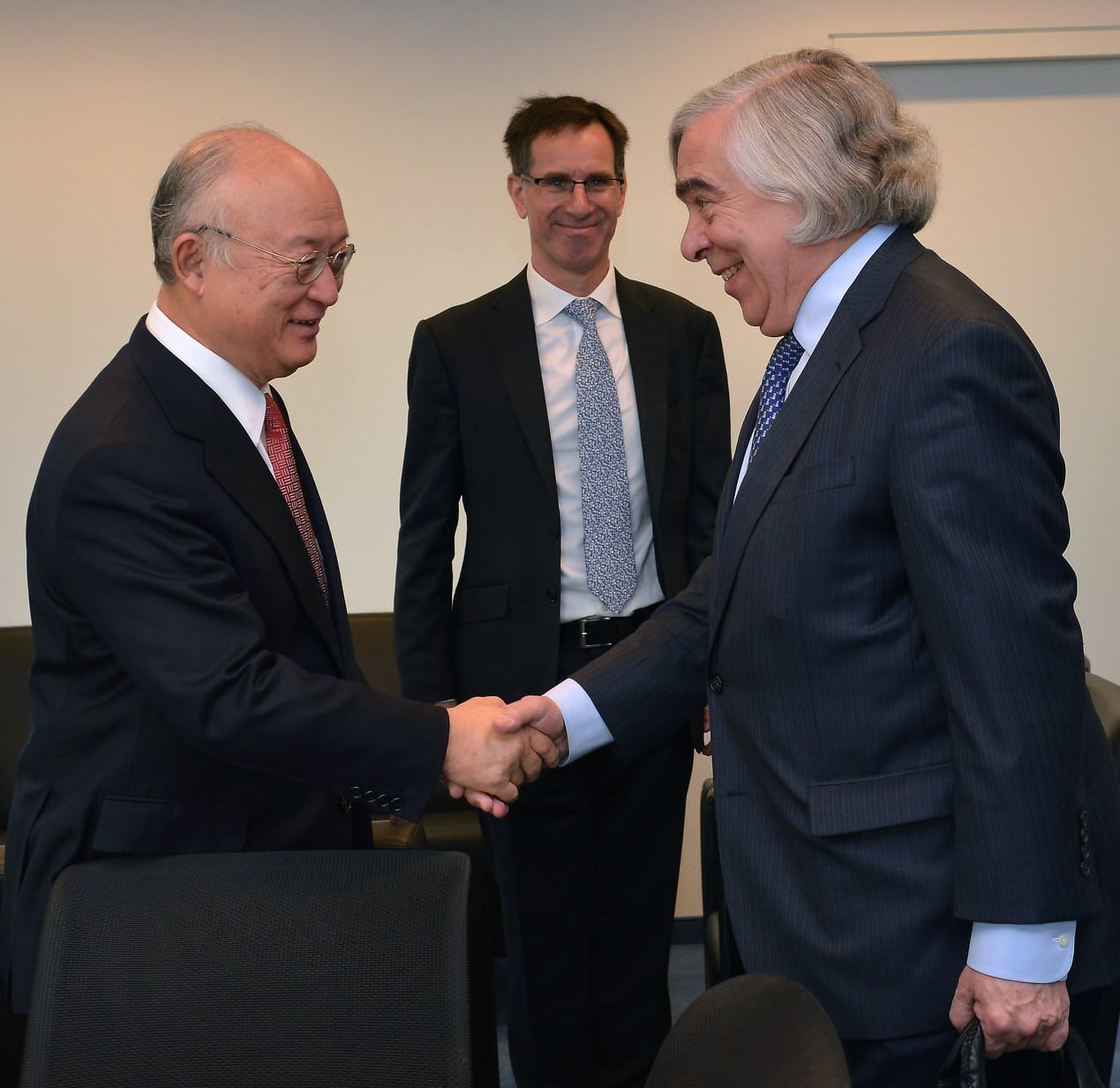

Meanwhile, the United States signaled this week its commitment to dispose of a total of 40 metric tons of plutonium. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz announced Monday at the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) International Conference on Nuclear Security that the U.N. nuclear watchdog would monitor the dilution and disposal of 6 metric tons of plutonium at the Savannah River Site – separate from the material covered by the PMDA – as part of this commitment.

The U.S. is “beginning consultations with the IAEA for the monitoring and verification of this process . . . to ensure this material will not be used again in nuclear weapons,” Moniz said. The Savannah River Site announced in late September that it had begun downblending the 6 metric tons, which will be sent to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico for disposal. A DOE-Savannah River spokesperson said at the time that a small portion of plutonium was being treated at the site’s K Area Complex; it was unclear as of Friday how much had been downblended.

The Energy Department said in a Monday statement that the dilute and dispose approach involves blending plutonium oxide with an inert material, packaging the diluted material in secure canisters, and preparing those canisters for permanent disposal in a geologic repository – the same process the Obama administration has proposed in place of the MOX facility.

The DOE statement noted the U.S. would “verifiably eliminate” the 40 metric tons, suggesting the IAEA would will monitor the dilution and disposal of the PMDA material as well. Countryman said, however, that this is not an effort to re-engage the Russians on the plutonium deal. “The United States will continue to dispose of the 34 tons we committed to, with IAEA monitoring, and the Secretary’s announcement was that we will do an additional 6 tons with IAEA verification,” he said. “We hope that the Russians will submit all of their plans to IAEA verification in this field. We are prepared to talk to the Russians at any time about the agreement, but it doesn’t change our plans.”

The U.N. agency’s safeguards monitoring involves measures including routine, ad-hoc, and other inspections, as well as placement of cameras and tamper-proof seals at facilities. It was not immediately clear which measures would be applied at the Savannah River Site.

Pavel Podvig, an independent researcher who heads the Russian Nuclear Forces project, said by email that the DOE announcement seems to imply the agreement could still be saved, but that the way this initiative is framed, “it probably falls short of what would be needed to generate some international pressure on Russia to return to PMDA.” Podvig said he believes strong steps are necessary to heighten pressure on Russia; he previously wrote that the U.S. could submit all key parts of the disposition process to IAEA monitoring, including the inert mixture agent or WIPP, as an example.

Moniz’s statement is “a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t seem to go far enough to make a real difference,” Podvig said. “There are also questions about whether the IAEA will be monitoring WIPP – probably not at this point.”

Some have suggested that a Russian decision to similarly submit its plutonium to IAEA monitoring could serve as a gesture toward building confidence on both sides. But Podvig said in an interview Thursday with NS&D Monitor that under the PMDA, “Russia has the right not to implement transparency [measures] if it’s not paid for.” The agreement involved U.S. financial support for international monitoring of Russia’s progress; without a deal, the Kremlin is not likely to implement this monitoring.

Although the United States would not be obligated to submit its PMDA plutonium to verifiable elimination if the deal were truly dead, Podvig believes it will continue to do so.

Moving Forward with Russia

“How to move ahead [with Russia] is too broad an issue at this time,” Countryman said, expressing hope for greater cooperation on nuclear security and threat reduction. “But the IAEA doesn’t need to help on that. The Russian Federation simply needs to change its approach,” he said. The U.S. has no new initiatives to this end but it does maintain contact with Russia on strategic stability issues, he added.

Russia’s 2014 incursion into Ukraine, which soured Moscow’s relations with the West, “is not just a blip on the radar,” but rather a destabilizing force in Europe, Countryman said. “It is not simple to go to business as usual as long as there remains a Russian Federation approach that existing multilateral commitments can be violated with impunity,” he said. “That’s a very big obstacle, and it is what the new administration will have to deal with.”

Countryman suggested additional priorities for the incoming Donald Trump administration to tackle after taking office on Jan. 20: the threat posed by North Korea, continued implementation of the nuclear deal with Iran, and strategic stability discussions – followed by arms reductions – with Russia.

“I think it is important for everybody in the world to understand that issues of nonproliferation and arms control have been consistently high priorities for every U.S. president for the last 60 years, and that these efforts on nonproliferation and arms control have enjoyed bipartisan support in the Congress for 60 years,” Countryman said. “I expect far more continuity than change in these fields as we transition to a new president.”