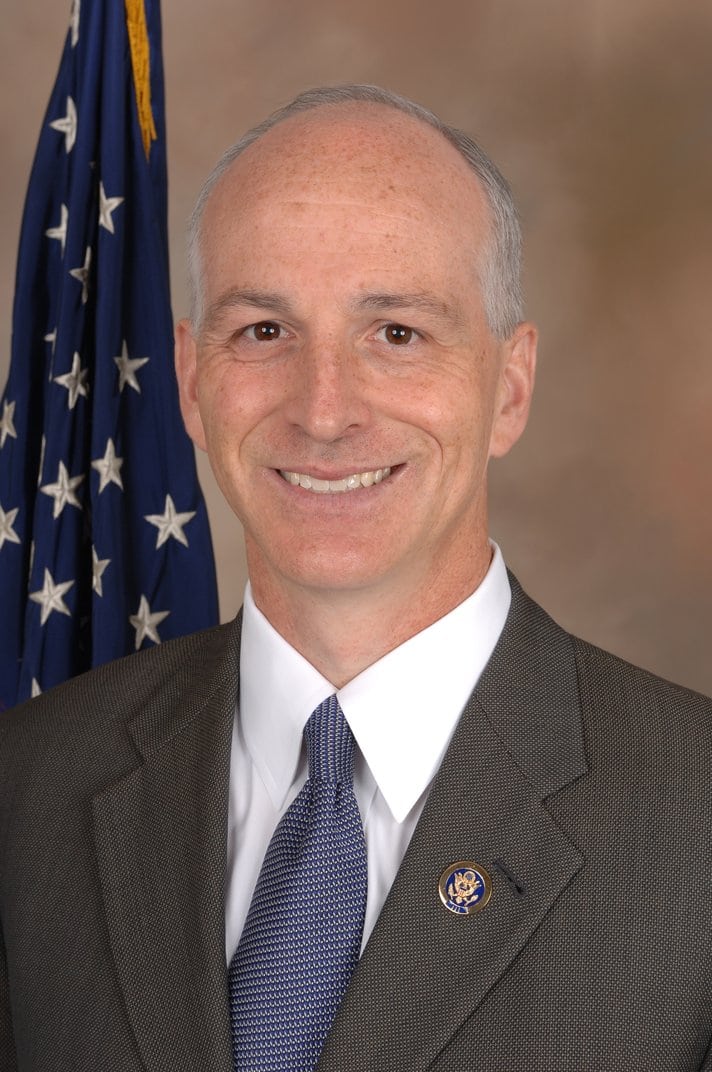

Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) wants to give state governors a firm voice in the Department of Energy’s reinterpretation of the federal definition of high-level radioactive waste (HLW).

In an amendment submitted to the House’s version of the fiscal 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Smith proposed prohibiting any DOE funding in the upcoming federal budget year “to apply the interpretation of high-level radioactive waste … unless, on a case-by-case basis, such interpretation is approved by the Governor of the State in which such waste exists.”

At the end of a review process that began last fall, the Energy Department said in a June 10 notice in the Federal Register it does not believe that all radioactive waste from reprocessing spent nuclear fuel should be treated as high-level waste. That potentially opens the door for new disposal approaches for some of this material, though the agency said it has not made any decisions on waste management.

Under congressional mandate, the Energy Department is supposed to place its high-level waste in a geologic repository for permanent disposal. It does not yet have such a facility, and the agency says some of that HLW has radioactive characteristics akin to transuranic or low-level radioactive wastes. Those waste types do not have to go into a geologic repository.

There is believed to be 90 million gallons of solids, liquids, and sludge left over from decades of U.S. nuclear weapons production, the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future said in 2012.

Critics say the Energy Department now could simply leave its HLW stocks in current storage locations at DOE facilities in Idaho, New York, South Carolina, and Washington state. Others worry that disposal sites such as the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico could now become home to material that was previously considered high-level waste.

The Energy Department has already said it would evaluate, under the National Environmental Policy Act, potential disposal options for up to 10,000 gallons of grouted or vitrified waste treated at the Defense Waste Processing Facility (DWPF) at the Savannah River Site (SRS) in South Carolina.

If Smith’s amendment becomes law, his home state is almost certain to disallow the federal reinterpretation of high-level waste.

“By taking this action, the administration seeks to cut out state input and move towards disposal options of their choosing, including those already deemed to be unsafe by their own assessments and in violation of the existing legally binding agreement. We will consider all options to stop this reckless and dangerous action,” Washington state Gov. and presidential candidate Jay Inslee (D) and Attorney General Bob Ferguson (D) said in a joint June 5 statement following the DOE announcement of its waste reinterpretation.

Undersecretary of Energy for Science Paul Dabbar said this week there are no plans to change the handling of any high-level waste in Washington state, The Associated Press reported.

Smith’s amendment is among dozens submitted to the House Rules Committee for the NDAA, which passed out of the lower chamber’s Armed Services Committee earlier this month. The Rules Committee is scheduled during the week of July 8 to consider the terms of the debate for the House bill, including which amendments can be considered on the floor.

Two other House NDAA amendments, one offered by Rep. Jeff Fortenberry (R-Neb.) and another by Rep. Pete Olson (R-Texas) would seemingly make it simpler for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), to move certain waste of foreign origin to the WIPP facility. The Fortenberry amendment specifically mentions waste from Russia.

The Senate on Thursday voted 86-8 to pass its version of the defense policy bill for the budget year beginning Oct. 1. That measure does not appear to make any reference to the high-level waste situation.

The NDAA establishes allowed spending levels for federal defense programs, including nuclear-weapon and cleanup managed by the Department of Energy. The actual funding is provided by separate appropriations bills.

Senate NDAA Agrees to White House Request on DOE Defense Cleanup

The Senate version of the NDAA authorizes roughly $5.5 billion, as requested by the White House, for defense environmental cleanup at the DOE Office of Environmental Management. Defense environmental cleanup makes up the bulk of the funding for the office’s portfolio of remediation projects at Manhattan Project and Cold War nuclear sites.

On June 13, the House Armed Services Committee NDAA called for a nearly $5.6 billion cap on defense environmental remediation spending for fiscal 2020. That is roughly $400 million less than recommended by the full House in an appropriations package passed last week covering the Energy Department and other agencies.

The funding bill in total seeks almost $7.2 billion for EM, covering the defense environmental, non-defense environmental, and Uranium Enrichment Decontamination and Decommissioning Fund line items. That would be roughly equal to the fiscal 2019 level, but more than the $6.5 billion requested by the White House in March.

The Senate has not issued its own funding proposal for DOE. Appropriations bills provide discretionary funding to programs that have been authorized.

The Senate NDAA instructs DOE to submit annual cost estimates for meeting remediation milestones, required by legal consent orders, at nuclear sites. This reporting measure was recommended earlier this year by the Government Accountability Office.

The Senate NDAA authorizes about $629 million in funding for the Richlands Operations Office, at the Hanford Site in Washington state. That is equal to Trump administration budget request, and $50 million less than the $679 million supported in the House Armed Services NDAA for the office that oversees contractor work at the DOE’s largest and most expensive nuclear cleanup project.

At the Hanford Office of River Protection, which oversees 56 million gallons of radioactive and chemical tanks stored in underground tanks following decades of plutonium production, the Senate bill approves $1.39 billion. That is s equal to the budget request and about $300 million less than the House Armed Services-passed NDAA.

The Senate NDAA, like its House counterpart, keeps the $1.46 billion limit for the Savannah River Site in South Carolina, as sought in the fiscal 2020 budget request.

Likewise, the Senate NDAA keeps the WIPP facility funded at no more than $392 million. That is the level sought in the DOE budget request and the House Armed Services NDAA.

Senate NDAA Seeks Changes at Nuclear Safety Board

Aside from nuclear weapons themselves, the Senate NDAA proposes major changes for the federal Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, which investigates current and former DOE weapon sites for health and safety issues.

The upper chamber’s NDAA would forbid board members from serving consecutive terms or from remaining on the board after their five-year term expires.

The Senate, citing findings from a 2018 report from the federally funded National Academy of Public Administration, said the five-member DNFSB appears to provide little value to Energy Department and suffers from a lack of collegiality among board members.

The House bill, on the other hand, would leave the board’s organizational structure intact, set a minimum number of permanent employees for the small independent agency, and codify that the board should receive “unfettered access” to DOE nuclear sites.

Both bills would authorize about $29.5 million for the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board. That is in line with its budget request for fiscal 2020.

The Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board has no actual regulatory power over the DOE, but can make recommendations to the agency, which must be publicly addressed by the secretary of energy.

Reporters Dan Leone and Wayne Barber contributed to this article.