A House-passed 2021 spending bill, which would provide the $816 million the National Nuclear Security Administration requested for its B61-12 life-extension program, would “impair” the government’s ability to deliver that refurbished nuclear bomb on time, a senior Pentagon official told Congress Thursday.

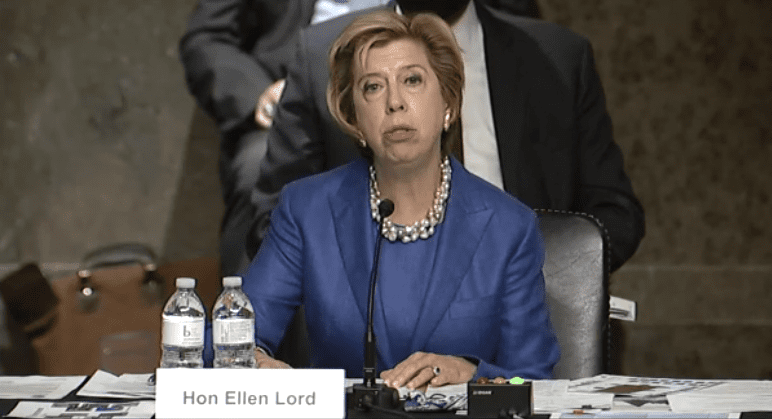

“It might not be intuitively obvious how that would affect certain programs because it’s a lot of the infrastructure and it’s a lot of the supporting work that’s done,” Ellen Lord, undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment, told the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Lord was not more specific in her testimony, except to say that under the House bill, B61-12 would hit delays as soon as fiscal year 2021, which starts in a couple weeks. A spokesperson for Lord did not reply to a request for comment about which line items in the House’s proposed 2021 National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) budget might delay B61-12.

The NNSA expects to finish the B61-12 first production unit in November 2021: between one and two years later than expected as recently as 2019, when the agency disclosed it would have to make new custom capacitors for the weapon because commercial capacitors slotted for use could not last as long as required. A first production unit is a proof of concept article, including a nuclear-explosive package, intended to prove a design is ready for mass production.

The House recommended $18 billion for the NNSA in 2021, which is more than $1 billion higher than the 2020 budget but about $2 billion less than requested for the fiscal year that begins Oct. 1. Most of the $2 billion the House recommended against appropriating was for plutonium pit production infrastructure that B61-12 does not need. Pits are the fissile cores of nuclear weapons, and B61-12, which will homogenize four other versions of the B61 bomb, does not require new ones.

The F-35A is supposed to be certified to carry two B61-12 bombs by the middle of the decade. The stealthy B-21 Raider that Northrop Grumman is working on, and which is supposed to debut next decade, would also carry B61-12, eventually. The aged B-52H does not carry nuclear gravity bombs any more.

Lord also said the House’s budget bills would blow up the timeline for fielding next-generation air-launched nuclear cruise missiles, and nuclear-tipped, silo-based intercontinental ballistic missiles: respectively, the Long Range Standoff Weapons being developed by Raytheon and the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent primed by Northrop Grumman.

The cruise missile would get $304 million from the House bill in 2021, $170 million less than requested, and the silo-based missiles would get $1.5 billion or so, which is $60 million under the request. The cruise missile’s budget request was lower year-to-year after the Air Force ended a competitive technology development round early, but the House’s proposed budget is lower still.

For the NNSA, the House’s appropriations bill is potentially less of a headache than the all-but-certain continuing resolution Congress appears poised to pass before the end of the month. The bill, according to reports, would stretch 2020 budgets into December: well after the Nov. 3 presidential election. That would hold the NNSA’s appropriation at an annualized level of just over $16.5 billion, leaving B61-12 with a budget that’s $23 million less, per annum, than what the House bill would provide. The Senate had not passed any 2021 appropriations bills at deadline.

Also at the hearing, Lord said that if the House’s budget became law, and the NNSA got none of the $53 million it seeks for the proposed new W93 warhead, the U.S. could not help the United Kingdom modernize the island nation’s fleet of nuclear-tipped Trident submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

“If the W93 was zeroed out, we couldn’t support the U.K. in the alignment of programs we have where we support them with non-nuclear as well as science and technology,” Lord said.

W93, which made a splash in the news this February when the 2021 budget dropped, is the eventual replacement for both of the Navy’s submarine-launched ballistic missile warheads, the W88 and the W78. The W93 would use a previously tested nuclear explosive package from the NNSA in a Mk7 aeroshell developed by the Navy. The U.K. uses Trident missiles in its current submarine fleet and would continue using them in the Kingdom’s new Dreadnought boats. Britain also relies on U.S. warheads, as modified by the indigenous Atomic Weapons Establishment.