After the Department of Energy released some 650 pages of details on its $16.5-billion nuclear-weapon budget request for 2020, the chair of the House Appropriations panel that funds the agency demanded more information on proposed weapons spending.

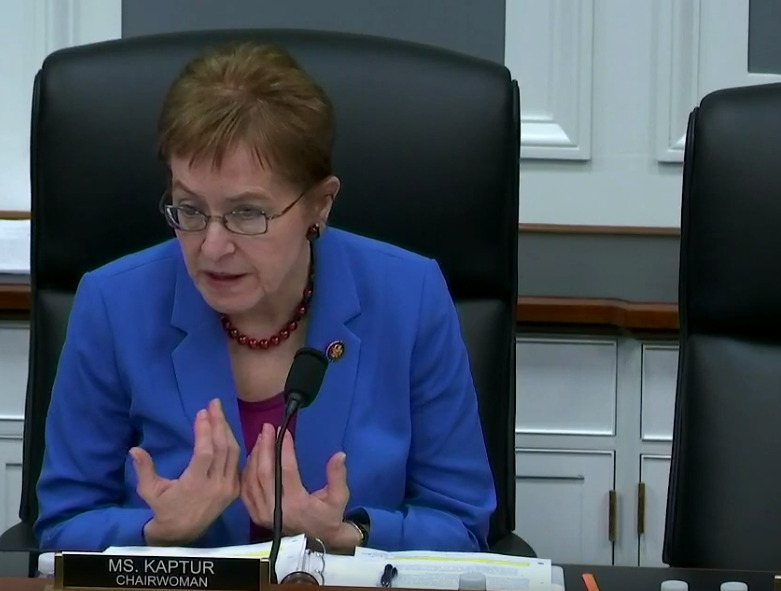

“With respect to nuclear weapons, this is not a budget that establishes clear priorities with a responsible plan to fund and execute those priorities,” Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D-Ohio), chair of the House Appropriations energy and water development subcommittee, told Energy Secretary Rick Perry during a hearing Tuesday on the agency’s latest spending request.

Kaptur asked whether Perry could provide any “ follow-on materials” about the proposed fiscal 2020 nuclear weapons and nonproliferation spending overseen by DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). Perry said the department would “work with” Kaptur’s office to provide “additional documentation” about the semiautonomous agency’s request.

Kaptur did not say during the hearing exactly what information she wanted that DOE did not include in the detailed NNSA budget request it released this week.

Kaptur “looks forward to hearing from NNSA on this at next week’s budget hearing,” a spokesperson said in a Wednesday email to Nuclear Security & Deterrence Monitor.

NNSA Administrator Lisa Gordon-Hagerty and senior agency officials are scheduled to appear April 2 before Kaptur’s subcommittee for a more detailed look at the proposed 2020 budget.

The NNSA requested some $16.5 billion in total for weapons, nonproliferation, and nuclear-Navy propulsion work for the budget year that begins Oct. 1. Weapons activities would get the biggest increase, if the budget request becomes law: nearly 12 percent, to almost $12.5 billion, compared with the 2019 budget.

During the hearing, Kaptur said she was concerned about the NNSA cutting “key nonproliferation programs.” She did not identify any by name, but her spokesperson said Kaptur was concerned about proposed reductions to programs in the agency’s Global Material Security account “that help prevent nuclear and radiological terrorism.”

The agency has proposed cutting Global Material Security to just over $340 million: 15 percent below the 2019 appropriation of some $405 million. The account’s domestic and international radiological security programs would take the biggest whacks: roughly 30 percent and 23 percent, respectively, for 2020 budgets of about $90 million and $60 million.

However, total nonproliferation spending would actually rise about 3 percent to almost $2 billion, if Congress approves the NNSA’s request. Within the account, the agency plans to continue converting the Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility (MFFF) at the Savannah River Site in Aiken, S.C., designed as a plutonium disposal facility, into a factory to annually produce 50 fissile warhead cores called plutonium pits by 2030.

Gordon-Hagerty has said her No. 1 nuclear security priority is building manufacturing infrastructure to produce 80 pits a year by 2030. To convert the MFFF for pit duty, the NNSA this year requested $410 million “for conceptual design and pre-Critical Decision (CD)-1 activities.”

It is the first new details about the planned South Carolina capacity, now called the Savannah River Plutonium Processing Facility, that the NNSA has published since announce plans to convert the MFFF last year.

Critical Decision 1 is the project management milestone in which DOE selects a single preferred means of meeting some goal and roughs out a cost estimate for that approach. A formal cost and schedule baseline follows at the CD-2 milestone. The NNSA did not say in its 2020 budget request when the pit plant might reach CD-2.

As for the other 30 pits a year the NNSA needs to produce under the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, the Los Alamos National Laboratory would crank them out in its Plutonium Facility, or PF-4.

The NNSA plans to expand PF-4 using funding from a pair of budget lines: the ongoing Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement project within infrastructure and operations, and the Plutonium Pit Production Project within directed stockpile work. In total, the programs would get about $188 million for 2020, if the NNSA’s budget request becomes law.

That is nearly 25 percent less funding than the $220 million that Los Alamos pit improvement got from Congress for fiscal 2019.

In a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee on Thursday, Gordon-Hagerty said the two-state pit strategy “is the most affordable and optimal way to get to the 80 pits per year by 2030.”

An engineering analysis, performed for the NNSA by Parsons Government Services and published last year by the citizen nuclear watchdog groups Savannah River Watch and Nuclear Watch New Mexico, said the two-state pit strategy could be almost twice as expensive as centering pit production at Los Alamos: about $30 billion compared with about $15 billion, over the program’s decades-long life.

Elsewhere in the budget, the NNSA requested $745 million to continue building the Uranium Processing Facility at the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tenn. That is about 6 percent more than the 2019 budget of roughly $700 million. The plant is due for completion by 2025 at a cost of $6.5 billion.

The DOE branch is seeking $10 million in the next fiscal year to finish work on the low-yield W76-2 submarine-launched ballistic-missile warhead. The funding, if approved, will pay for “completion of production and delivery of all W76-2 warheads,” according to the budget request.

The NNSA finished building the first W76-2, a modified version of the recently refurbished W76-1 warhead, in February. The agency plans to deliver the first warhead to the Navy by Sept. 30. The W76-2 budget for 2019 is $65 million; the requested funding down ramp reflects the planned end of the program.