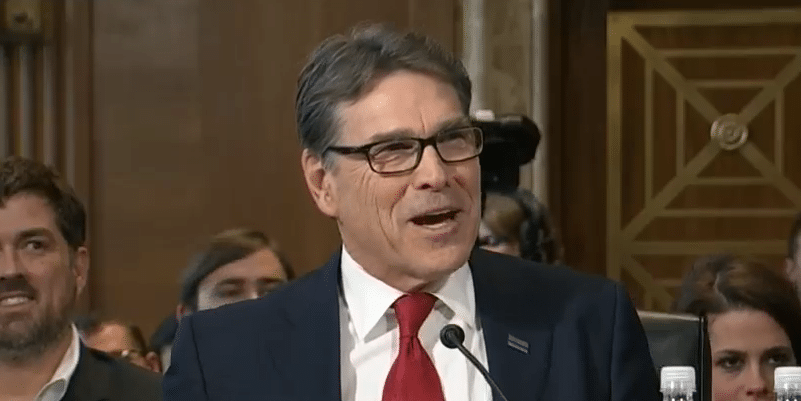

A highly critical congressional report this week could open the door for Energy Secretary-designate Rick Perry to reverse the Obama administration’s finding that the Energy Department should build a deep-underground disposal site specifically for nuclear waste…