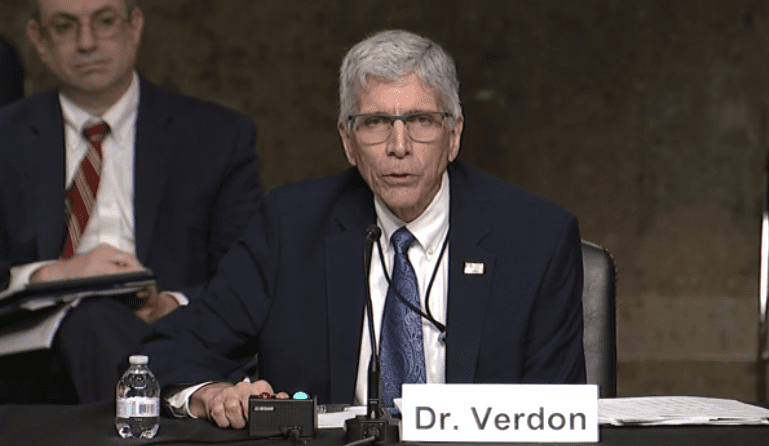

The acting head of DOE nuclear weapons programs on Thursday passed on a chance to say that a planned plutonium pit factory in South Carolina will cost as much per unit as a cheaper pit factory planned for New Mexico.

The National Nuclear Security Administration…